Schools are losing experienced Teaching Assistants and struggling to recruit more.

They’re losing teacher experience as well of course; but the loss of teacher experience is grabbing headlines, and I worry that whilst we tend to the fractures in teacher recruitment and retention, we overlook the internal haemorrhage of TAs.

TA roles are wide and varied, and importantly, they’re not teachers. It’s easy for someone to agree with Tim Leunig’s scepticism of TA value, but I think anyone working with TAs – as a colleague or with their own children, knows it’s not as simple as that. Of course, there’s a truth to Leunig’s comments. Some children do experience too much time away from qualified teacher instruction, some teachers do pass over responsibility for complex needs to support staff; but the ‘dinner lady turned TA’ trope* is a lazy way of presenting the role that does nothing to support the genuine case for TA retention.

Since that infamous ‘low-impact, high-cost’ graph, there has been a lot of work done on how to better deploy TAs. Opportunities for TAs to develop have increased and, whilst still needing a lot more work, TAs are professionalised more than they ever have been before. We can do specialist NPQs, can join the Chartered College of Teaching, there are signs of easier routes to degrees and ITT (if that’s what they want).

There’s an increasing understanding that high quality teaching for pupils with SEND is high quality teaching for all. Scaffolding, modelling, chunking, visuals, manipulatives, supporting self-regulation, questioning, repetition, retrieval, lowering extraneous load: we’ve been doing it for years and there’s a huge wealth of expertise leaking out of schools.

TAs are often the long-term experience in a school. Historical lack of progression routes means that many have stayed in the same school for years, or perhaps done the same level role in several different settings – seeing things from different angles, subject to each coming and going fad. TAs are often local to the school community and know the area, they know parents, they know siblings. They have years of professional relationships with outside agencies and support networks.

But they’re leaving. It matters that pay is so poor. It matters that they’re publicly perceived as unqualified and unknowledgeable. It actually matters that it’s seen that the only valuable reason for being a TA is to get into teaching. TAs feel many of the same pressures that are leading teachers to leave so of course they’re going. It’s clichéd to say they can earn more working in a supermarket, but they can. And many do. And that’s before the increase in work-from-home opportunities. Teaching Assistant is a rewarding and worthy job, but you do have to eat and pay for a roof over your head, which really does make the decision for a lot of people.

The result of so many experienced people leaving, and fewer experienced people applying for new jobs, is an unrecoverable loss of what makes many schools work for so many children and families. Successful TAs have long come from all sorts of backgrounds and often get into it as supply or as life shifts, but there’s increasingly no one left to show them what to do, to model the nuances of engaging with different needs, the subtleties of supporting pupils to achieve – gaining confidence and not leaping in too soon. When I started doing all this I was surrounded by people who had 15+ years under their belt and it was a masterclass.

If we ignore the loss of Teaching Assistants, and lose the ability to nurture new talent, we’ll feed into the already damaging narrative that’s it’s a low-pay-low-quality position, or merely work experience before ITT. It’s more than that and the solutions are complex, but I worry we’ll only notice the bleeding when it’s too late.

*There are plenty of ‘dinner ladies’ who work as TAs. It’s a legitimate career pathway that we shouldn’t ignore, and should actually promote, and there’s no reason why a ‘dinner lady’ or TA can’t have the highest levels of qualification. Some of them even go on to teach and to lead schools and all of them can make the most massive difference, actually.

Ten years ago, back when Brain Gym was the only Brain Gym and there were no The New Brain Gyms; back when you could count the number of teacher-authored books on your fingers; back when the authors of today’s teacher-authored books worked in a classroom (😉): researchED happened.

That ridiculously early get up to drive down to London was the start of something brilliant. I counted it up and I’ve been to 32 researchED events and spoken at 20 – including 6 in other countries. I’ve learnt so much from so many amazing people that my brain has ached. I’ve seen unknown speakers who were astounding, and I’ve seen well-known speakers who were rubbish. I’ve sat in a pub and made friends I see year after year, in all sorts of parts of the country; in all sorts of parts of the world. I’ve turned into the sort of person who always has a presentation clicker in her handbag.

Yesterday I looked at the hashtags for that first event. Turns out there were three on the go: #researchED2013 #rED2013* #rED13. The buzz is visible in every tweet and follow up blog post. Some of the ideas people were discussing have been used so often since that they’re INSET cliché, and some of the people discussing those ideas are doing things I’d guess they’d not have dreamt about then.

*Do have a search for them, but this one got confusing as Taylor Swift fans were using it to go nuts over something related to her Red album.

researchED has changed over the years, as have the people attending and speaking, and the zeitgeist it’s part of has changed education in this, and hopefully, other countries. There seems to be a new event every week now, but the national conference is always something really special.

After that first early start we learnt our lesson and opted for a proper weekend away, but it’s still an amazing thing, with amazing people, and new things to learn about every single time. There are several people I normally look forward to seeing who I know won’t be there tomorrow, but I know they’ll be following this year’s hashtag and I know there’ll be other events, at other times. Maybe one day, even New Zealand for something Very Sensible Indeed.

See you all bright and early!

Happy 10th Birthday researchED 🥳

After years (and years) running literacy interventions and supporting GSCE Englishes, I have nothing to do with that now in my role (obvs literacy is everyone’s job but you know what I mean). I still like to read around and engage with English PD and pedagogy – something I’m increasingly aware feeds into how pupils work in art, particularly as our KS4 haven’t done English Lit this year and it turns out I reference literature analysis skills A LOT and they really can forget how to do it #BringBackPoetryAndShakespeare. Anyway, I often pick Englishy sessions at conferences and yesterday was no different as I was speaking at the Teaching and Learning Leeds conference held at The Grammar School at Leeds.

Chris Curtis used his #TLLeeds23 session to speak about the importance of inference in reading instruction and what his school have done to approach this. Lots of schools have launched into obsessions over vocabulary and are increasingly looking towards fluency, but Chris argued that for students to be genuinely engaging with what they read, we really need to be focussing on inference.

One of the problems he highlighted was that a lot of reading is about the exam – ‘here’s the question, read the text’ stuff – and this changes the way students read. Those getting grades 2 and 3 are merely skimming and scanning for easy answers, not actually reading the text. It struck me that it’s exactly the same for my grade 2/3 art pupils – they’re skimming and scanning when they see an artwork. What they need is to develop their inference skills for ‘reading’ art in the same way they need to for reading texts.

Chris was clear that he wasn’t just talking about reading in English, and offered ways to adapt the theory and approach in other subjects; but I’m not talking about reading text in art. Reading text does look different in Art and I’m interested in how to make this better, but inference in art doesn’t just come about from texts, it’s central to evaluating pieces of art themselves, and I wanted to think about using Chris’s ideas about approaching texts to support students with making inferences about artworks.

So let’s go through some of the stuff Chris talked about and where I think it could work with art engagement.

He used Anne Kopal’s 2008 work on Effective Teaching of Inference Skills for Reading (pdf) to give an outline of the different types of inference he would be talking about.

What is being connected?

Coherence inferences – within a sentence, like switching to using pronouns once someone has been named; they need to know who the pronoun refers to.

Elaborative inferences – drawing on their own experience or prior reading to make connections between sentences

In analysing art, coherent inferences could come from identifying different features of an artwork, describing individual elements. Elaborative inference would involve drawing on knowledge about an artist, when a piece was made, other works by the same artist perhaps.

Where in the text?

Local inferences – sentence or paragraph level inferences (coherence as above, connecting actions to causes etc).

Global inferences – looking at a text as a whole and using local inferences to identify overarching themes.

In art, this could be the difference between focussing on particular elements or techniques within a piece, and combining these to evaluate how these make up the work as a whole.

When in the reading process?

On-line inferences – drawn automatically as a student is reading, in the moment.

Off-line inferences – drawn after reading, through retrieval or when engaging with further information.

For art this might be about an initial ‘reading’ of an artwork and making connections to further artworks, or even themes in their subjects that add to their interpretations and understanding.

Approaching the text

Chris went through several examples of how to approach a text by activating students’ prior knowledge and scaffolding the process of reading a text to explicitly make inferences. He talked about tethering their knowledge to simple ideas such as whether something might be a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ thing, based on what they already know – rather than try to overload them by pre-loading them with too much pre-teaching. He discussed his process of first summarising (local inference) before looking at the whole piece (global inference) when approaching fiction texts, and how they change this for non-fiction to identifying feelings (to force inferences) before thoughts (avoiding personal opinion).

His example from geography used an image as a stimulus and moved through a sequence of initial thoughts, to slowly revealing pairs of key vocabulary words to build knowledge (coherence and local inferences) before introducing supportive text-based material (elaborative inferences) and then asking pupils to elaborate and rationalise their conclusions (global inferences).

The use of an image as the stimulus was an obvious connection for me with art and offers a guide for how it might work in practice.

Let’s use something we’ve all seen before and consider how a student might approach it.

My grade 2/3 student would perhaps select it for a project on ‘time’ or ‘dreams’ or maybe something like ‘change’ if we’re getting more interesting. They’d see the clocks, try and copy them, do a print, take some photos of pocket watches… It’s OK but fairly formulaic and definitely ‘skimming and scanning’. Now let’s try and tease out some inference.

1. What can we see? (Local inferences into global inferences using elaboration)

- Several melted clocks with a branch and cliffs and water in the background, could be a beach.

- The clocks look like old fashioned ones so it could be an old painting.

- One clock on a bare tree. Bare trees are often dead.

- Fly on one clock and ants on another. Flies hatch on dead bodies, ants crawl over things looking for food.

- If it’s a beach, the white thing could be a beached whale. It looks like it has a large closed eye.

- Perhaps it’s about death and the clocks have stopped and life is fading into the distance.

2. Introducing vocabulary pairs to develop explanation.

- Cool – Warm

- Portrait – Landscape

- Foreground – Background

- Shadow – Light

- Distorted – Accurate

3. Introduce supporting (text?) information

- Movement: Surrealism – it’s not real, the things don’t necessarily belong together?

- Title of artwork: The Persistence of Memory – it’s in the mind, a dream, a memory?

- Year: 1931

4. Rationalising/ Elaboration

This is where they might move away from their more literal interpretations for their projects and start to open up some more sophisticated themes…

- Time – running out of time, memories, past, present, future

- Dreams – hopes and dreams paused through fears, nightmare, reaching for the light, landscape that is a portrait of someone’s mind, post WWI shifts in dreams

- Change – hard to soft, light to dark, life to death, hopes to fears

As a project moves on, the on-line inferences are used to develop off-line inferences and built into project themes. Maybe they’ll use this to make off-line references to something else.

Finally, we use (as Chris talked about) their deeper use of inference to promote complex thinking, hypotheses and supposition – eventually to the point where we promote macro-thinking and they can discuss flaws and contradictions within and between pieces.

It all seems pretty obvious, but it’s really hard to unpick a process that you find so automatic. Making your thinking visible is a crucial part of modelling, and I hope I’ve shown that the framework Chris and his colleagues have developed for doing this with text is adaptable for thinking about it in art. I’m certainly going to put some more consideration into how this can be supported, and I’ll certainly keep going to the Englishy conference sessions.

We use professional development to bring about educational improvement, and it’s important that we evaluate whether what we’re doing is working. We have limited resources, both time and money, so knowing our ‘best bets’ are doing what we think they will, and knowing how they impact pupil outcomes is important.

I’ve long been frustrated that evaluation of PD is so ‘surface’ – reduced to a likert scale questionnaire that asks you, two minutes after you’ve put your notebook away, to rate the impact of a workshop on your teaching. Effective PD evaluation is something I’ve thought about on and off for years now, gathering new bits, adding ideas together as I work on different things. Last weekend I went for it and presented where I’m at to a room packed with people at researchED Birmingham who didn’t argue back at me, so perhaps there’s something in this. I said I’d write about it, so here’s an abridged version.

What are we evaluating?

How can we take what we know about effective CPD and the way we learn to inform how we evaluate and evaluate better?

We are gaining an ever greater idea of what makes for effective PD. The DfE’s 2016 Standard for Teachers’ Professional Development draws the evidence into five areas:

- Focus on pupil outcomes

- Underpinned by evidence

- Collaboration and challenge

- Sustained over time

- Prioritised by leadership

And the EEF’s 2021 ‘Effective Professional Development’ guidance report presents a series of mechanisms essential for effective PD:

- Building knowledge

- Motivating teachers

- Developing teaching techniques

- Embedding practice

Of course, one of the challenges of implementation is that the ‘ideal’ never fits all situations. Rob Coe and Stuart Kime wrote in their editorial for Impact in 2021, “…there is very little in education that can be implemented according to a recipe or manual – and remain effective.” and “…implementing complex programmes that require adaptation (i.e. most educational interventions) is unlikely to be successful without effective, real-time evaluation.”

We have an ‘ideal’ process of PD-to-impact, but could the process of PD-to-impact look different for different people? Of course, when something’s different for different people it becomes a step harder to evaluate.

PD looks different for different people

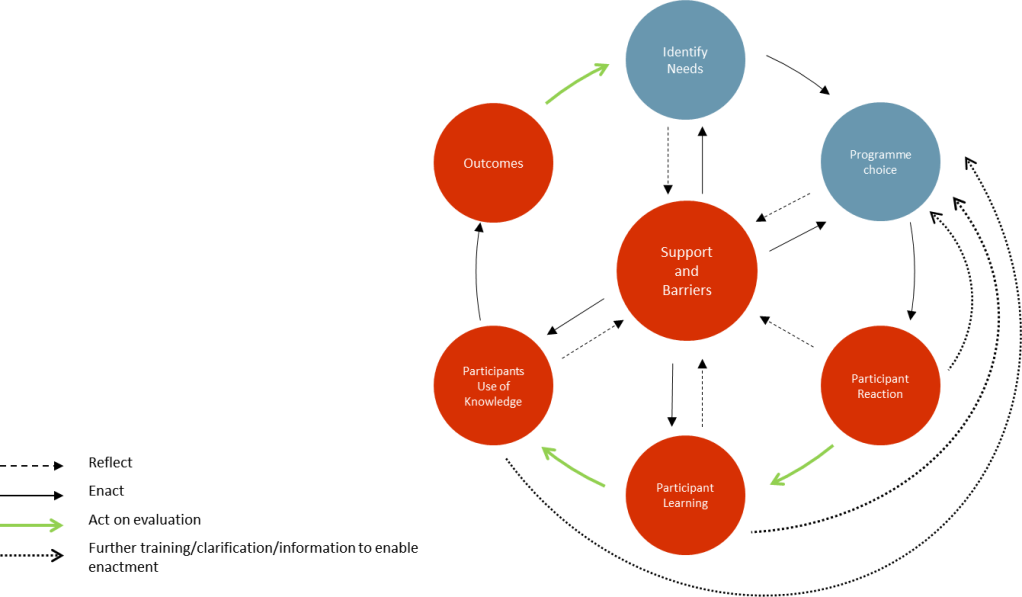

I’ve written before about individual ‘depth of practice’ and routes through the learning process, drawing on (my favourite) table from David Weston and Bridget Clay’s ‘Unleashing Great Teaching’ (2018), and Argiris’ Ladder of Inference. One of my mental rabbit holes has led me to explore different models of learning, and I have been repeatedly dawn to this non-linear, non-sequential model from Clarke and Hollingsworth (2002) that allows space for different routes through processes of reflection and enactment in four domains: external, personal, practice and consequence, and offers explanation of how different people process the same learning events.

Traditionally, lots of people follow Guskey’s (2000) linear model of evaluation:

- Participants’ Reaction

- Participants’ Learning

- Organisational Support and Change

- Participants’ Use of New Knowledge and Skills

- Student Learning Outcomes

I like the detail of this in Guskey’s book but something has never sat quite right with me about it, and points made by Coldwell and Simkins (2011) get close to addressing my niggles. There’s an assumption that each successive level is more informative than, caused by and correlated with, the previous one, and that failure comes from inside the PD event. The other thing they point out is that ‘organisational support and change’ is more of a condition for change than a consequence of it.

Having considered individual, non-linear models of learning, I’m wondering if PD evaluation itself isn’t linear.

My cycle of CPD evaluation

Taking a pack of post-its and a table-top, I have developed my (conceptual) non-linear model of PD evaluation. The features of Guskey’s model are still there, however I’ve changed ‘Organisational Support and Change’ to ‘Support and Barriers’ and placed this at the centre of the process. The cycle draws on Clarke and Hollingsworth’s non-sequential pathways of learning, and offers an opportunity to take an individual journey of reflection and enactment between domains. My prediction is that the benefits of this are that evaluation is part of the whole cycle, from planning and implementation, and ensures organisational support from the start. It makes it possible to add additional learning, interlink multiple PD threads, adapt programmes to individual needs, and turns a tick-box process into one that’s more of a checklist. It’s still possible to track Guskey’s traditional model through, but where evaluation shows someone needs to go back or repeat a step, they can. Where someone comes into a PD programme half-way through implementation, their own process has a path.

During my rEDBrum talk I went through each element and offered an explanation of how this looks in practice, but for space reasons I’m just going to focus on my latest area of (obsessive) investigation here.

What is a barrier?

Until recently, I accepted ‘barriers and support’ was pretty obvious. Now I’ve been thinking about it in more depth and I’ve started to think about potential types of barrier. Individual, organisational, programme content, external? Is a barrier when ‘what works’ is missing? Are there things we can address in advance?

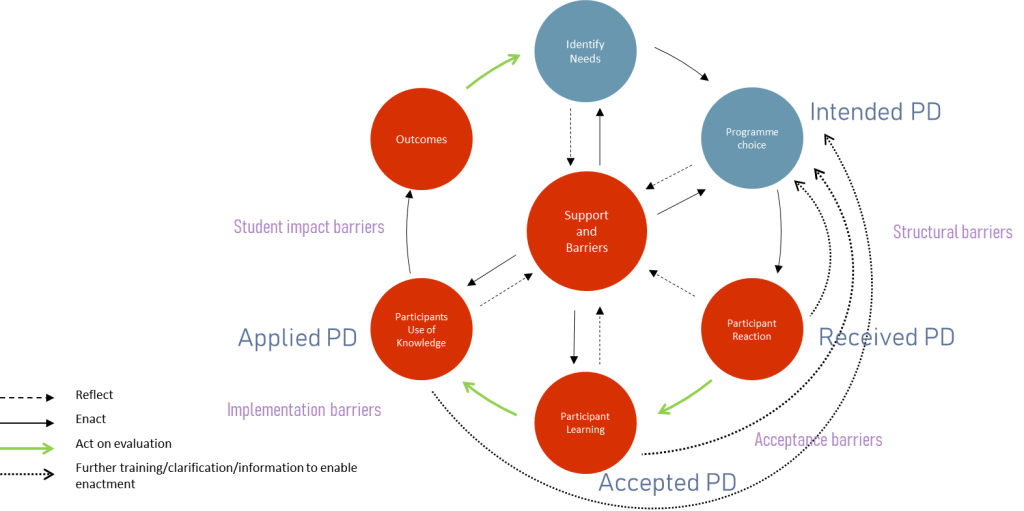

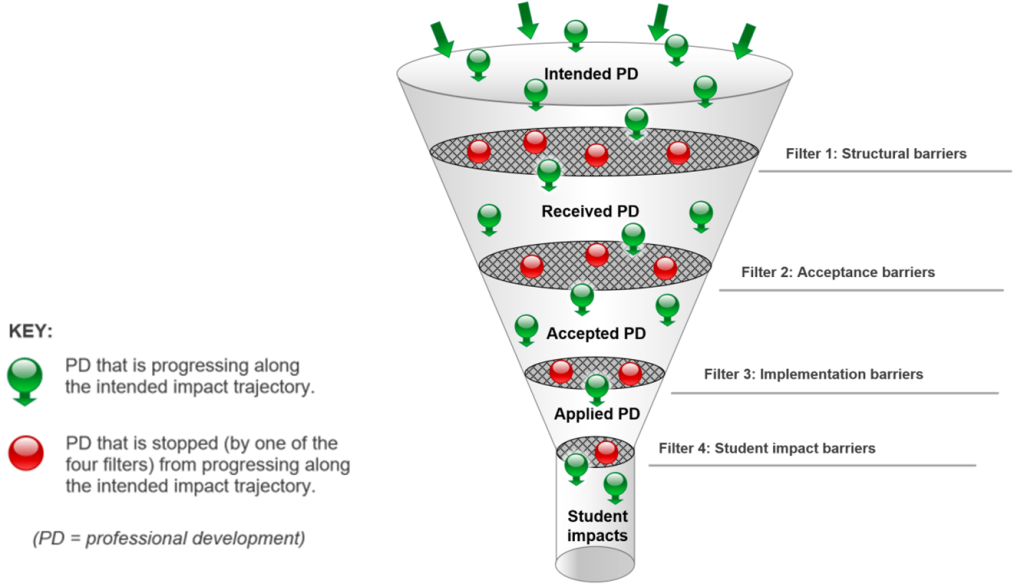

I found this (amazing) paper by McChesney & Aldridge (2019) where they introduce their ‘conceptual model of the professional development-to-impact trajectory’. They spoke to teachers in Abu Dhabi about their experiences of PD, and what prevents them from enacting what they have learnt, and they demonstrate the relationship between intended, received, accepted and applied PD, with structural, acceptance, implementation and student barriers.

I see connections with the Ladder of Inference, the routes different people take through the same PD activity, the influence of internal and external factors, and I started to map where the PD mechanisms outlined in the EEF’s guidance report are present or missing.

My next step was to think that if we can identify what these barriers could be made up of, we can place these onto the evaluation cycle and narrow down what we want to look out for and when. I’ve started to go through a range of sources to find evidence for different barriers:

Effective CPD

- The effects of high-quality professional development on teachers and students (Zuccollo and Fletcher-Wood, 2020)

- Effective teacher professional development: new theory and a meta-analytic test (Sims et al, 2022)

Culture

- A culture of improvement: reviewing the research on teacher working conditions (Weston et al, 2021)

- Why do some schools struggle to retain staff? Development and validation of the Teachers’ Working Environment Scale (TWES) (Sims, 2021)

CPD Evaluation

- Evaluating Professional Development (Guskey, 2000)

- Level models of continuing professional development evaluation: a grounded review and critique (Coldwell & Simkins, 2011)

- What gets in the way? A new conceptual model for the trajectory from teacher professional development to impact (McChesney & Aldridge, 2019)

SEND

- Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools guidance report (EEF, 2020)

I’m in my early stages of this process but already have a table of potential barriers that I’ve been able to map onto McChesney & Aldridge’s structural, acceptance, implementation and student barriers.

What it looks like in practice

Here’s where I’m at with the process for now. In advance of PD event – set culture/environment, include PD mechanisms. During PD event – position evaluation to check against known barriers in the order they’ll come up, act on evaluation. After PD event – check against goals. Not rocket science, but I’m hoping I’m onto something.

There’s plenty more for me to think about. I want to look for other barrier categories – particularly pupil barriers as McChesney and Aldridge only theorised this and I’ve only had a surface look at barriers related to SEND. I want to think about how to support evaluations at scale (can I make pro-formas to make it easier?), and I want to think about ‘support’ in the same way I’ve looked at ‘barriers’. I’m also interested in how to add mechanisms yourself if they aren’t ‘in’ CPD events (and if that’s possible).

Clearly I’ve not got space here to go into as much detail as I did in my rED presentation, and I have a lot more thoughts on this, but I hope this sets out a rationale for my ideas and how my various chains of thought have come together. The benefit of not being able to go into everything in blog form is that hopefully I can present on it again, maybe having thought on some of my next steps…

References (from my rEDBrum presentation, not all cited in this post)

Argyris, C., Putnam, R., Smith D.M. 1985. Action Science: Concepts, Methods, and Skills for Research and Intervention. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Clarke, D. and Hollingsworth, H., 2002. Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and teacher education, 18(8), pp.947-967.

Coe, R. and Kime, S., 2021. An evidence-based approach to CPD. Journal of the Chartered College of Teaching, 13.

Coldwell, M. and Simkins, T., 2011. Level models of continuing professional development evaluation: a grounded review and critique. Professional development in education, 37(1), pp.143-157.

Effective Professional Development guidance report, EEF (2021)

Fishman, B.J., Marx, R.W., Best, S. & Tal, R.T., 2003. Linking teacher and student learning to improve professional development in systemic reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19, 643-658.

Guskey, T.R., 2000. Evaluating professional development. Corwin press.

Guskey, T.R., 2002. Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8, 381-391.

McChesney, K. and Aldridge, J.M., 2019. What gets in the way? A new conceptual model for the trajectory from teacher professional development to impact. Professional development in education, 47(5), pp.834-852.

Sims, S., 2021. Why do some schools struggle to retain staff? Development and validation of the Teachers’ Working Environment Scale (TWES). Review of Education, 9(3), p.e3304.

Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, H., O’Mara-Eves, A., Cottingham, S., Stansfield, C., Goodrich, J., Van Herwegen, J. and Anders, J., 2022. Effective teacher professional development: new theory and a meta-analytic test (No. 22-02). UCL Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities.

Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools guidance report, EEF (2020)

Standard for teachers’ professional development (2016) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/standard-for-teachers-professional-development

Weston and Clay, 2018 Unleashing Great Teaching https://www.amazon.co.uk/Unleashing-Great-Teaching-David-Weston/dp/1138105996

Weston, D., Hindley, B., & Cunningham, M. (2021). A culture of improvement: reviewing the research on teacher working conditions. Working paper version 1.1, February 2021. Teacher Development Trust.

Zuccollo and Fletcher-Wood (2020), The effects of high-quality professional development on teachers and students, EPI.

We have a lump of stuff to teach, and we need to group it, but how do we know where and when to group it?

We traditionally see thematic curriculum models in primary settings with a sharp switch to subject-specific teaching in secondary. It makes sense that teachers can’t all do it all to a high level, so we have to split it up, and it makes sense to have common ‘splits’ to allow staff to specialise their knowledge and transfer between settings.

This year we have moved from split key stages 2, 3 and 4, to two phases – Yr3-8 and Yr9-11, with a topic-based curriculum up to Year 9 (with a few stand-alone subjects). I’ve done a lot of work around curriculum design over the last few years and my initial reaction to extending topic into KS3 was reserved. I understand that our pupils’ needs are different to mainstream practice but I know how important it is to maintain subject integrity – maybe more so considering the narrow opportunities our pupils get outside of school.

Daniel Muijs talk at researchED Nottingham “Curriculum, Science and Transfer: What do we know?” gave me a different perspective and has set me thinking. He discussed how thematic approaches to curriculum can foster knowledge transfer with careful consideration of connection, coherence and context. Some subjects are inherently more multi-disciplinary and Mujis gave the example of geography which is made up of things like geology, meteorology and economics.

We don’t teach these as discreet subjects to begin with. We teach core knowledge and group threshold concepts together which gives students the preparation to go on and specialise later. I’m wondering if all subjects are actually thematic until we really specialise? Muijs questioned where specialisation starts and ends, and as I’m concerned about maintaining the integrity of subjects as part of a topic, I’m left thinking whether, if we’re already blending subjects together to making new ones, how much does it matter?

What actually is a subject anyway?

It’s usual for some subjects to have their own space in primary (English, maths, science) but not others. It’s usual to separate everything in secondary (ideally with cross-curricular links). If we can successfully group ‘subjects’ into ‘topic’, or multiple subjects into a less specialised subject, what makes a subject a subject? Instead of separating everything at secondary, are there better times to specialise for different subjects?

Now. I’m not saying hundreds of years of refining has got it wrong; clearly more than a week’s pre-occupation after a Saturday conference session have gone into this. I’m just wondering if there’s a way to frame how we present a thematic curriculum as a subject in its own right and might this form a helpful scaffold for curriculum development?

Dylan Wiliam uses the term ‘subject disciplines’ in his 2013 publication, ‘Principled Curriculum Design’, stating that, far from being randomly selected, “the traditional school disciplines represent powerful – and qualitatively different – ways of thinking about the world. The word ‘discipline’ is important here because it connotes both a subject, and the commitment that is needed to acquire the ways of thinking emphasised by the subject.”

I think those two factors are what I keep thinking about. If we are creating a new ‘subject’ of ‘topic’ for more novice pupils, do we need to be grouping things that have a similar way of thinking? Or, can we group threshold concepts for a wider range of subjects to create a new subject for the less experienced? Actually, unless ‘topic’ is a discreet ‘subject’ where you don’t differentiate between traditional subjects, does it just risk becoming an exercise in squeezing stuff in/saving time on the timetable to the detriment of the subjects we’re trying to teach?

Can we create a new subject?

Do we first need to split existing subject disciplines in to their component branches?

What subjects does this work with?

Daniel Muijs mentioned geography. History might be world history, classics, archaeology, folk law; RE is the study of world religions, moral issues, philosophy; Citizenship and PHSE spring to mind too. Is it the less hierarchically structured subjects we can do this with?

Can we rearrange these broken down subjects into new subject combinations? If you can make genuine connections between branches and sequence them, does that work as a ‘subject’? If you look at the different branches and they don’t connect, then they are part of a different subject?

Is it a question of if branches/themes are fundamental to a number of other subjects, they get their own subject? Or is it important to practice these things in lots of different domains? More important, perhaps?

Are there forgotten subjects?

We sometimes teach ‘humanities’ as one subject, or a cycle of subjects. Normally the ones I’ve mentioned actually. A quick Wikipedia search gives me anthropology, archaeology, classics, linguistics and languages, law and politics, literature, philosophy, performing arts, visual arts that also fall into this group. Could we make a richer thematic subject curriculum from these?

Back in the olden days, a liberal arts education was the order of the day: the (humanities) trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) and the (scientific) quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy). Can we learn from that to group our domains of knowledge?

Moving forwards in time again, it’s not uncommon to have ‘social sciences’ as an academic field. The branches here are numerous, but include sociology, anthropology, archaeology, economics, human geography, linguistics, management science, political science, psychology, and history – starts to look a bit like ‘topic’…

So, which subjects normally get included in ‘topic’? Should ‘humanities’ be one subject? Should we have ‘social sciences’? When is it important for students to know they are studying a specific subject? Is it important? Subjects are more than the way we categorise what we want them to learn.

I think I don’t like ‘topic’ as a timetabled subject because it seems wishy-washy. We need to avoid the ‘that wasn’t in history, that was topic’ conversation, and ‘topic’ can be anything – seems like lumping stuff together rather than considering it, particularly if it’s in secondary. Could/ should we have a more formal term? Multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary, cross-disciplinary – the differences? Could we just call ‘Topic’ social sciences if maths, English, science etc. are being taught separately? Would it make a difference if it seemed like a formal subject?

Exams

Now, if you’ve got this far, don’t laugh at me now. I wondered whether this whole ‘creating a new subject from bits of other ones’ thing could make for a different way of examining pupils.

Terminal exams are one of the things that limit what can happen with a thematic curriculum. Exams happen in specialisms which means that, however pupils experience subjects further down the school, they need to be able to access a specialist course. If the curriculum is covered well and the integrity of subjects maintained, that shouldn’t be an issue – to go back to the example of geography, pupils who study geography are able to access geology as a specialism.

We need pupils to have a way to specialise, do more in depth, ditch stuff they don’t like. We need to be able to compare pupils against each other. Could pupils do common modules and different combinations are different exam subjects? The water cycle might fit into biology, geography, meteorology, geology – can we teach it and how it fits into different subject disciplines at the same time?

I don’t know how it would work in practice of course. It may be that the majority of modules are fixed in a school but pupils could specialise a few bits and then sit the ‘geology’ or ‘philosophy’ exam rather than ‘geography’ or ‘RE’. Basically, I’ve spent time thinking about this and time looking at Tom Sherrington and Oliver Caviglioli’s Teaching Walkthrus with their lovely mix and match hexagons.

I just need to go to the pub

I’ve clearly spent a week just thinking of more questions. What I really need is one of those post-conference pub sessions where you thrash everything out and resolve all the issues in education. Instead, I have a slightly shifted perspective, no answers and more blummin’ education books winging their way to my shelves.

On the issue of ‘topic’, I think it’s probably possible to build a highly effective curriculum to a high level, but it’s going to be really hard. I suspect that if we could give it a ‘proper’ subject name then it might be easier to define what needs to be included, maybe even to set out the core knowledge and wider curriculum links. I don’t know. It’s just me thinking.

My last researchED post was written between #rEDBrum20 and what should have been, but wasn’t to be, #rEDHan20. I wrote about what has become a big part of both my personal and professional life, and whilst we’ve had a wealth of online CPD to choose from since then, nothing is quite like a face-to-face event.

Hollywood likes to depict the end of world-changing events with scenes of ‘walking out, blinking, into the Sun’, but I think we know now that there is no ‘walking out’ moment, it’s just keeping going and feeling a bit more knackered and fed up with it all whilst grabbing the bits of Sun we can and hoping it’s finally going to get a bit better. Yesterday we had a live-in-person, face-to-face bit of Sun in the form of the researchED National Conference, 2021, and it was blummin wonderful.

The event was smaller than more recent national events but there was still the same, familiar buzz about the day. I was speaking in the first session (successfully managed to hit play on Tom’s welcome message) and didn’t have a plan of any speakers I had my heart on seeing so once I’d done my bit I sort of floated into sessions as I went. With strict limits on numbers in rooms it worked well to avoid disappointment, and I had a really good day.

So. My Day.

First up for me was Tom Richmond and ‘Do lesson observations really work?’ Loved it. A hearty investigation into the evidence base with lots of references to follow up on and a conclusion with caveats. I’ve often wondered if having a word with support staff would be just as good a way of looking at effective teaching and, with a few exceptions, I’m still pondering it. Undercover TAs – is that a thing unions would go for…?

Next I saw Cassie Young talking ‘SEND and Sensibility: What lessons can we learn from lockdown’ where she gave a superb overview of some research she’d undertaken with SENDCos, teachers, parents and pupils to find out what was happening during lockdown and what we can take away from it. The session addressed behaviour and environment, the language we use, modelling with the use of technology, and relationships with parents and carers. It was a great example of walking the walk with practitioner research engagement and something I’d like to see more of at researchED conferences – particularly the regional ones where I find some sessions can slip into running through pedagogical techniques.

My third session was finding myself in Paul Kirschner’s talk on generative learning strategies. This was more like researchED presentations I’ve been to before (for obvious reasons). I did quite like his thoughts on summarising and using it as a technique to almost work backwards from if you’re wanting to make sure an argument is logical and ordered effectively. Going to mull that over a bit more I think.

My most random session (didn’t look at the programme before wandering in) was Tamsin Moore and Richard Slade discussing insights from Star assessments and the research being undertaken to look at progress over the last couple of years. They have a wealth of historic data that has been used to track primary and secondary progress along with pandemic data. There are three reports out so far with another two due this year – not gonna lie, a lot of it was tiny on the screen so I’m going to have a proper look and I think it’ll be interesting to see what they find for different groups (particularly after hearing Cassie’s more anecdotal evidence of lockdown learning).

Last, but definitely not least, I went to see Richard Adams read out the ‘worst edu-PR emails ever’ and it didn’t disappoint. After a day thinking hard it was a joy to hear some of the absurdities that cross the desks of education editors, and the undertone of headline statistics that are presented as evidence but really don’t take much knocking down. I’d happily sit through another hour of this and am also wondering whether to suggest school needs a slime-room to calm the kids down.

As always, the actual final session was in a pub and you know what, it was the best thing in the world. I got to giggle with my friends who I haven’t seen for too long and I really needed that.

At any researchED you can see big names and familiar topics, support your friends in their sessions or dip in with people you haven’t heard of; I think I did all of that this time. Who knows what the next few weeks and months will bring and whether we’ll have to wait again to come together. Days like yesterday take a lot of hard work and behind the scenes organisation and I don’t think it has ever been worth it more for that little glimpse of Sun.

After 14 months predicting what the ‘new normal’ will be, there are now glimmers of old normality returning; and whilst some are jumping headlong into every lift of restrictions, others are more hesitant.

It’s understandable that some of us will struggle to come out of being locked down and have to readjust to new routines and social expectations, but what seems to have come as a surprise is that this rebalancing is exhausting.

Recently, Rachel Rossiter tweeted that for someone whose ‘life flows with established patterns based on the school year’ having this taken away has created an ‘unsettled equilibrium’. This clearly resonated even beyond education as followers replied with how the sudden shift from regular life to the home office and no social reprieve had messed with their natural order of things.

My theory is that we’ve had to shift where we have our monotony because we’re not getting it where we normally do. There’s been so much change in the parts of life that have pattern (like school), where we’d normally do the ‘new’, on-a whim stuff to break the monotony (like going for a meal or weekend away) we have created a new, unfulfilling, monotony through never ending Netflix.

In their book ‘Switch: How to Change Things When Change Is Hard‘, Chip and Dan Heath discuss research that shows ‘self-control is an exhaustible resource’ and when we ask people to change things, we’re asking them to alter behaviours that have become automatic. Change involves conscious self-control of new behaviours and if this self-control is exhausted it’s harder to think creatively, inhibit impulses and ‘persist in the face of frustration and failure’. They conclude this section of the book by saying: ‘Change is hard because people wear themselves out. […] What looks like laziness is often exhaustion.’

Whilst they are discussing change in terms of personal goals or at an organisation level, it’s not a huge leap to see how this relates to the past year. Covid has meant adapting to some serious changes. Some of these were massive and happened very quickly but there have been other, smaller, ongoing changes that seem relentless. We have coped with this by reducing change where we can; to avoid exhaustion, we’ve shifted where we experience change.

We’ve created a new pattern to our lives and probably dealt as well as we have with social freedoms being taken away because that’s where we’ve been able to reduce old ‘change’ to enable processing of the enforced changes. We’ve developed a new monotony but because it isn’t in the right place it doesn’t feel right and doesn’t quite do the trick. It’s hard to come out of lockdown because there’s still too much change going on; what we feel is internal resistance to un-lockdown may actually be fatigue to change.

Whilst schools are starting to get back to the regular pattern of things, we’re still not ‘normal’ and as we enter a time of year that always comes with changes, this year the prospect of change may be more exhausting. As people’s capacity for change varies, plans for the new year may be causing additional anxiety. Whether this is roles or colleagues changing, new management, or the drip-feed-trailing of changes as a big surprise to look forward to; leaders need to bear in mind that what looks like laziness or resistance to change, could actually be exhaustion.

People want security and that’s even more likely at the moment. We crave security – something to fall back on when we’ve tried something new. In ‘Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking‘, Susan Cain discusses the idea of ‘restorative niches’ as a place to go to ‘return to your true self’. For introverts like me this can be taking my break away from other people, working in solitude at 6am on a Saturday, or scheduling down-time after socially demanding events. Everyone will be dealing with changes to their lives differently and getting back to the normal of going out, hugging, road trips and holidays is what many of us crave, but after so much uncertainty, more uncertainty of change takes more of a toll and we can help ourselves by identifying where we will find our own restorative niche, and where we can support those around us to access theirs.

Our safe structure and pattern of life has changed. And it hasn’t just changed and stuck there, it’s shifted and twisted. We’ve gone along with it because we have to but it’s exhausting and all we want more than ever is a pause. Breathing space to get used to a rhythm – either the old one or a new one; but a regular one. We need to work out where we fit into the new pattern so we can get back to doing those nice, random things that take us away from the monotony, and enable us to do the monotony really well.

One of my favourite researchED presentations was a session where Tom Sherrington worked through the process of how, as a headteacher at the time, he had used a specific piece of research to inform decisions on their school’s reading strategy. I’m a big fan of using stuff that’s already out there as a starting point. There’s no point trying to come up with something completely new when the chances are someone’s already done it, tried it out and presented it in a lovely evidence-informed bundle with a pretty graphic. Having briefly mentioned at a Research School event last week how I was supporting our SLT/MLT to used different evidence based resources to develop our school’s common principles for teaching and learning, I thought others might like to see how this worked in practice – so here we go.

The task

In my capacity as school Research Lead and trust Development Lead, I was invited to support our SLT and MLT as they developed their principles for classroom practice ahead of our February INSET. Their starting point was the autumn QA process (observations and book looks as far as I know) and they wanted to establish a set of ‘non-negotiables’. Things like the use of learning objectives and marking systems were talked about (nothing crazy or new) and the term ‘non-negotiables’ was used as a sort of place holder in lieu of a better term as there was recognition from the start that this shouldn’t be something that restricted colleagues, particularly where subjects work in different ways.

Aside from being curious to see what had come out of the QA, it was interesting to see how each of the leaders prioritised different needs – some from personal preference, others from their specific key stage needs. I’m naturally a bit of a Devil’s advocate in these situations (I swear people thing I just disagree with everything but I promise I don’t!) so I wanted to try and get them to think about whether the features they perceived as being signs of an effective classroom really were that and really dig into their rationale. Using the example of ‘learning objectives on the board’, we unpicked what it was about that that was actually supporting learning and how the same can be achieved in all lessons (including practical subjects that may not use a board all the time) with a more general principle.

The inspiration

After our Trust Improvement Partner discussed using the SEND Code of Practice and features of quality first teaching to help set out the principles I went straight to the woman who knows, Rachel Rossiter, and asked what she thought we should be looking at. Her suggestion was to take the Education Endowment Foundation guidance report ‘Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools’ and look at the recommendations around QFT in recommendation 3. Then we could look at Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction and explore how the EEF guidance and Rosenshine marry up. Once we’d done this, we could explore what this looks like in our own school with our needs, and think about our areas for improvement.

This is exactly what I needed. Having something to frame the discussion made it much easier to focus on core priorities and stopped the question being ‘Out of everything in the whole world, what are our priorities?’ and became about how we can reflect on what we do in line with an evidence base. The other thing that became apparent was that, talking through the QA notes, all the things that had been identified for improvement were already on the list of positive things that were happening. This was now a process of identifying our ‘golden threads’ and promoting these for more consistency rather than looking at the more negative things and telling people to change their practice completely.

Building on these ideas and the links to evidence, I mapped everything we’d got so far with some other documents to try and draw out common elements to form the principles. In the end I had the QA categories identified by one of our MLT, the EEF SEND guidance, Rosenshine’s Principles (handily grouped by Tom Sherrington), the collated QA comments, and, as it seemed useful to find some alignment with early career learning, and links to the teacher standards and the new NPQ frameworks, I included the areas of focus from the Early Career Framework. I put everything together in one happy table (here as a pdf) to support the final principles.

The principles

- Respect for relationships, behaviour and the environment

- Learning intentions are clear, shared and understood by pupils

- Lessons are well sequenced

- Use of appropriate scaffolding to promote independence

- Assessment and feedback are used to promote pupil progress

They aren’t designed to be anything new, just recognising our best practice and offering an opportunity to re-focus on what we do well. This should support current colleagues but also act as a clear vision for prospective and future colleagues.

The principles are intentionally broad as we felt it is important that they are achievable in all lessons. When anyone walks into one of our classrooms these principles should be enacted even though that will look differently across the school. So, for example, ‘learning intentions are clear, shared and understood by pupils’ might still be seen through the use of learning objectives, but it might be through feedback, review previous material, questioning or sharing examples. ‘Assessment and feedback are used to promote pupil progress’ might be through marking books but instead of having a fixed expectation for marking, it recognises the different ways we assess and feedback to pupils, including in lessons that don’t use exercise books.

The INSET

As part of our end-of-half-term INSET the principles and guiding rationale were introduced to colleagues. In key stage team bubbles (2,. 3 and 4) colleagues were given time to discuss the teaching and learning common principles and look at what’s working well and areas for development. We made the full documents that had informed the development process available, alongside a selection of supporting evidence, ahead of the INSET with the intention that these would be available for people to access in support of their discussions but also remain available as we embed the principles and seek to improve our practice.

I’m looking forward to seeing how each key stage captured their discussions from the day and I hope that they found it valuable to unpick their practice in line with the evidence base. From my experience of the group I was in and a brief conversation (distanced, obvs) with a colleague from another key stage, I think different groups found different levels of value in the process. Reflecting on that, I wonder if the task was perhaps too wide for some people or maybe not explained clearly. I think it’s easy to look at principles like this and feel that you’re already doing it and don’t need to improve anything, so by keeping an eye on professional autonomy there’s also a balance to find with how much guidance to give to exploring the ‘why’ something works in order to improve.

The use of evidence to frame the decision-making provided much needed clarity for leaders with different experience and views. The principles may change and be refined, particularly in light of the feedback from colleagues following the INSET day, however one of the benefits of sharing the evidence more widely is that decisions can be pinned more easily to that and not to individual leaders’ opinion – if there’s something we disagree with, it’s the research we can argue with, not the leaders.

I’m hoping that one thing the feedback gives us is a really good direction for professional development priorities for the future and we can begin to develop a common language around teaching and learning that all colleagues feel are relevant to their practice.

References

Education Endowment Foundation Special Educational Needs in Mainstream Schools Guidance Report – https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/tools/guidance-reports/special-educational-needs-disabilities/

High quality teaching for pupils with SEND (additional resources) – https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Publications/Send/EEF_High_Quality_Teaching_for_Pupils_with_SEND.pdf

Principles of Instruction: Research-based strategies that all teachers should know (Barak Rosenshine) – https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/periodicals/Rosenshine.pdf

Early Career Framework – Policy Paper – https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/early-career-framework

Our first art adventure since February was a trip to Tate Liverpool and their ‘Constellations’ exhibition is AMAZING.

The series presents works by how they relate to each other rather than by individual artist, movement or chronologically. Each ‘constellation’ has a central piece of art that acts as a ‘trigger’; connecting the themes and relationships between other pieces. Alongside each constellation is a word cloud showing a visual representation of the common themes across the series of pieces.

In some ways this reminded me of the Glenn Ligon exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary a few years ago which showed Ligon’s work alongside the pieces that had inspired his art. It offered a fresh perspective and opportunity to see a broader range of work, bringing to life the artists’ process rather than reducing it to a step-by-step/do it for the next grade ‘formula’.

One of the most challenging things I find teaching GCSE art is supporting pupils to make links between ideas, artist and artworks and in many ways I think these skills are central to the whole qualification. I want to see if I can use the idea of ‘constellations’ to explore different ways of creating topics and allow pupils to articulate connections between work – making connections less obvious and yet more tangible.

With this in mind, I’ve created my own constellation using Rachel Whiteread’s ‘Ghost’ as a trigger for what I think has turned into an exploration of ‘memory’. Feel free to let me know what you think and how your own constellations might look.

Rachel Whiteread – Ghost 1990

I chose this for my trigger as Whiteread’s work provokes quite an emotional response from me. The piece is a cast of the interior of a room. It is not a representation of the room, it is the essence of the room. Everything that was the room, everything that happened there, the memories of the room, are contained, captured, the space of the room is frozen in time. Whiteread has described it as causing ‘the viewer to become the wall’ and I find this fascinating. It makes me consider whether a room is the walls and features, or is it about what goes on within the space? Is the ‘Ghost’ that of the room or is it the viewer, removed from the memory of the space?

Pompeii casts

The haunting casts of the negative space left by a physical form of the bodies that perished during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD. As Whiteread has created a room that renders the viewer as part of that room, the ash surrounding the bodies bore witness to the creation of a space that has now been revealed.

Antony Gormley – Concrete Works: Sense 1990-93

The casts in Pompeii were taken from the negative space left from decayed bodies and Gormley creates the negative space of a crouched body within a cube. It is a representation of the space the body takes up; the viewer sees indications of the void within.

Herculaneum restoration

The town of Herculaneum was destroyed during the same eruption of Mount Vesuvius that saw for Pompeii however many of the organic materials in Herculaneum have been preserved including wooden beams, doors and window frames. The burnt timbers capture a moment in time. They appear timeless in their place and have been preserved in their position with wire and through conservation.

Mona Hatoum – Remains of the Day 2016−18

Everyday objects have been covered with chicken wire before they have been burned. The resulting pieces are reminiscent of sudden events such as the eruption of Vesuvius or an atomic blast, leaving behind common, domestic artefacts as they stood in one moment. The wire prevents the charred remains from disintegrating, however unlike the beams of Herculaneum they have been preserved before they have been burned. Elements that would have fallen and been discarded are trapped in their positions; a trapped memory, shadows of their previous form and are perhaps more akin to the negative forms left in the ash at Pompeii.

David Nash – Pyramid, Sphere, Cube 1997-98

These connect to Hatoum’s work through their materials but also their representation of space, movement and matter – continuing the thread of time and memory through the constellation. The burning of the wood transforms a solid object into something more fragile, questionning its permanence. These shapes appear frequently across David Nash’s work and I find we use them a lot in school projects. On a basic level the simplicity gives pupils something relatable and achievable to base their work on, but there’s something deeper to dig into and that’s why I’ve chosen them as part of my constellation. Nash talks about how we have a physical relationship with three-dimensional objects – we know the scale, can relate ourselves to the objects, and with two-dimensional pieces we have a mental relationship as we fill in the gaps and connect with our interpretation. Moments in time will evoke different reactions for different people and this collection of six pieces combines these physical and mental responses.

Lynda Benglis – Quartered Meteor 1969, cast 1975

Whilst the ‘Pompeii’ arm of the constellation has a theme of negative space, this arm has more of a focus on creating art using the form of a space. This piece was originally created by pouring foam into the corner of a gallery before it was cast in lead. In Tate Liverpool’s exhibition this is used as a trigger for a constellation that explores materials however what struck me was the form of a piece that has captured the space in which it was created – the walls and floor of the original gallery – and is now placed in different spaces, hiding its underlying origin.

Rosanne Robertson – Chasmschism 2019

This series takes plaster casts of cracks in stones to create new works. The shape of the natural form is identifiable and yet neither the stones nor the cracks are the piece. Robertson describes how the works connect ‘qualities of stone, water and other aspects of nature with our gender expressions, sexuality and identity’ and I feel that this is an evolution of the literal representation created by Whiteread’s Ghost, to the adoption of a space to create a new form in Benglis’s Quartered Meteor, into the creation of a new piece that retains the memory of it’s origin yet is not defined by that.

Richard Long – A Line Made by Walking 1967

Rather than the physical representations of objects or beings, this arm of my constellation is about the traces left behind by events. Richard Long’s piece is a record of his physical interaction with a landscape, the flattening of grass as he has walked over it repeatedly. This is the sort of art that lots of people struggle to understand and yet I think it is just another way to record a relationship with the environment. Whiteread captures a space in time, the casts of Pompeii reveal a frozen moment and Hatoum preserves a memory. Long’s series of walks are recorded on maps, in found materials and in photographs but the physical traces such as this line are temporary, fleeting, and will be lost in time.

Covid Traces – An Idea

This is a photograph I took in our local Asda supermarket last week. Barely visible is a mark on the floor where a large sticker marking the direction of the aisle that was in place during lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic to regulate customer movement around the shop. Our world is currently full of signs, stickers and markers to remind us of how to behave and they are put there perhaps without consideration of what they represent. As much as they are practical now, they are fleeting and I think it would be interesting to record the traces that these measures leave behind. Once the markings wear off the pavement, the tape arrows removed from walls that take paint with them and leave a scar, the sticky residue left behind on carpets in schools where desk zones were marked. These are the things that will record the change in our environment from this moment.

Lots of us have taken the opportunity to dip into the vast array of CPD that has sprung up during lockdown. Whether it’s collaborative discussions with the Teacher Development Trust’s #CPDConnectUp, daily conference sessions from researchED with #rEDHome, online courses from the likes of Seneca Learning or FutureLearn, or simply taking advantage of the array of publisher discounts that have popped up – there really seems to have been something for everyone.

Some schools have directed people to specific courses or made suggestions of things staff may like to look at, but with any of these there’s a risk that CPD is done as a way to keep busy and our eye on how this fits into the bigger picture is lost. So how can we make sure that what we’re learning during lockdown is useful and informs our practice in a meaningful way once we return to the classroom in a more regular fashion? In many ways this is similar to the ways we should approach our own learning at any time.

Types of CPD

It’s worth thinking about the different types of CPD that you are doing to help have an idea of where it fits into the bigger picture. Rough categories you can use include:

- Mandatory and procedural – those routine things like learning how to use a new online delivery or report system perhaps

- Subject-specific (including SEND) – deepening your own knowledge, maybe with a particular curriculum topic in mind

- Pedagogical – broad teaching methods

- Pedagogical content knowledge – how the broad teaching methods can be specifically used in your subject

- Wellbeing – some things aren’t necessarily linked to the classroom but still valuable!

- Personal career development- more structured (probably ongoing) courses such as NPQs or degrees

Structure and purpose

It’s also worth having think about the structure and purpose of the CPD you’re doing. Is it a one-off activity or an ongoing programme of work, and is it intended to have direct or indirect impact on your practice? Most people will think about this in black and white – that one-off presentations or courses are more likely to be ‘nice to do but easily forgotten’ and ongoing learning with continued opportunities to practice are preferable. I actually think it’s more nuanced than that and, particularly at a time like this, we can make connections between the variety of learning we are doing now, along with previous learning and plans, to curate our own, personal, ongoing CPD.

At the moment it’s likely that most of what we do is going to have an indirect impact on practice. Of course, lots of people will have engaged in CPD that focuses on remote delivery and learning for pupils which will have a more direct impact, but there are lots of things that might wait until we’re back with more pupils and a more regular structure that, at the moment, seem more indirect so it’s worth considering the bigger picture.

Your own needs

In more usual times, the depth of engagement in a CPD activity we engage with is more likely to be linked with our prior experience and the level of expertise we want to build up. The first time we come across a topic it’s appropriate to get some one-off information and a general overview of it. As we become more experienced we introduce more view-points, more detailed information and we try things out, sometimes collaboratively, and seek feedback. The more experienced we become, the more automatically we apply our knowledge and the more adaptive it becomes to different situations.

Everyone will be at a different point in this process and it is useful (at any time, not just lockdown) to have an awareness of where you are with the learning you are doing and by reflecting on where you need to build your personal experience and expertise you can make any learning opportunity part of your personal, ongoing ‘programme’.

Obviously this all sounds well and good but how do we actually undertake this reflection in a useful way?

Think about the types of CPD you’ve done

Some of us might have rushed in and done the lot. Make a list of all the CPD you’ve done. It’s useful to have a record – you don’t have to use all of it right away but think of how you’ll ‘bank’ it for later.

Why did you choose it? Were you directed or was it a personal choice? Were you looking for more information on a common subject, exploring a new theme, finding out more about something you’ve have prior experience of CPD on? Do you just like the speaker or did you just have the FOMO need to ‘collect them all’?

Where are the links or common themes? This should include links between the things you’ve done as part of your lockdown learning, but also think about wider learning. Can you make connections between other things you’ve read, had an INSET on, been working on with your PLC or enquiry project?

What next? Where are the opportunities for further learning? Are there recommended books to read, links to follow up or ways you can use your learning to adapt ‘back at work’ plans? Once you’ve taken stock of the learning you’ve done so far, can you identify where you could narrow your focus and be more selective, or have you found new ideas you want to explore in more depth?

The more we make these connections, the more we stop CPD becoming ‘one-off’ and the more we can see how it connects to our practice.

Evaluation

We can’t necessarily evaluate impact in practice or on pupil outcomes directly at the moment but we can focus on our initial reactions to CPD and begin to identify our personal next steps and barriers (organisational, personal or with the CPD itself) that may need to be resolved to support any implementation.

You might find it useful to frame your reflections and evaluation through the areas of guidance covered in the Standard for teachers’ professional development:

- Focus on improving and evaluating pupil outcomes – self-review before, during and after CPD event to identify where pupil outcomes can improve and how this CPD might support that.

- Underpinned by robust evidence and expertise – How is/was CPD underpinned by evidence? Can you follow up references? Why should the recommendations work and how should they be implemented?

- Collaboration and expert challenge – Use discussion boards within CPD, share your reflections and wider learning, think about how to share with colleagues. How can leaders support this?

- Sustained over time – Where does it fit with your existing learning and how does it support your ongoing plans?

- Prioritised by school leadership – Where CPD activities have been directed, ask where it fits in to the bigger picture. Look at your school’s priorities and consider how your learning can support these.

To support recording learning reflections and evaluation, you might find it useful to use Cornell note taking or fill in a PMI grid with your positive, negative and interesting follow-up reflections.

Pitfalls

With so much potential for learning away from the checks and balances that conversations and collaboration with colleagues affords, it’s of course important to be aware of things to avoid. Be aware of your own bias. There can be a risk if we dip in and out of things we already find interesting and agree with (confirmation bias) that we place increased authority on speakers and organisations we like (halo effect) and once we’ve done that one-off course or read a book, we suddenly find ourselves an expert and rush to change all our systems for September (Dunning-Kruger effect).

With any CPD you do – lockdown or otherwise – take your time to evaluate claims, check your bias and the bias of those delivering CPD. Leaders need to be aware of this too. If you’ve directed staff to complete online learing, be aware that this doesn’t make them an expert and plan how you will support follow-ups before creating any snazzy new whole-school responsibilities!

Take-aways

So many of us are finding that the combination of having (slightly) more flexible time and the veritable explosion of generous online CPD opportunities means we’re dipping into all sorts of things we might not ordinarily have done and this is fantastic. We need to make sure that we harness this learning and use it to benefit our collective practice. Whilst the suggestions here are bent towards lockdown learning, with any CPD it is valuable to evaluate your own learning journey and where a CPD event fits with your needs as well as the wider picture of your school and pupils.

As we shift from our different patterns of working back to a more regular in-school routine, consider what you have learnt now and take it forward to plan and support your ongoing development.